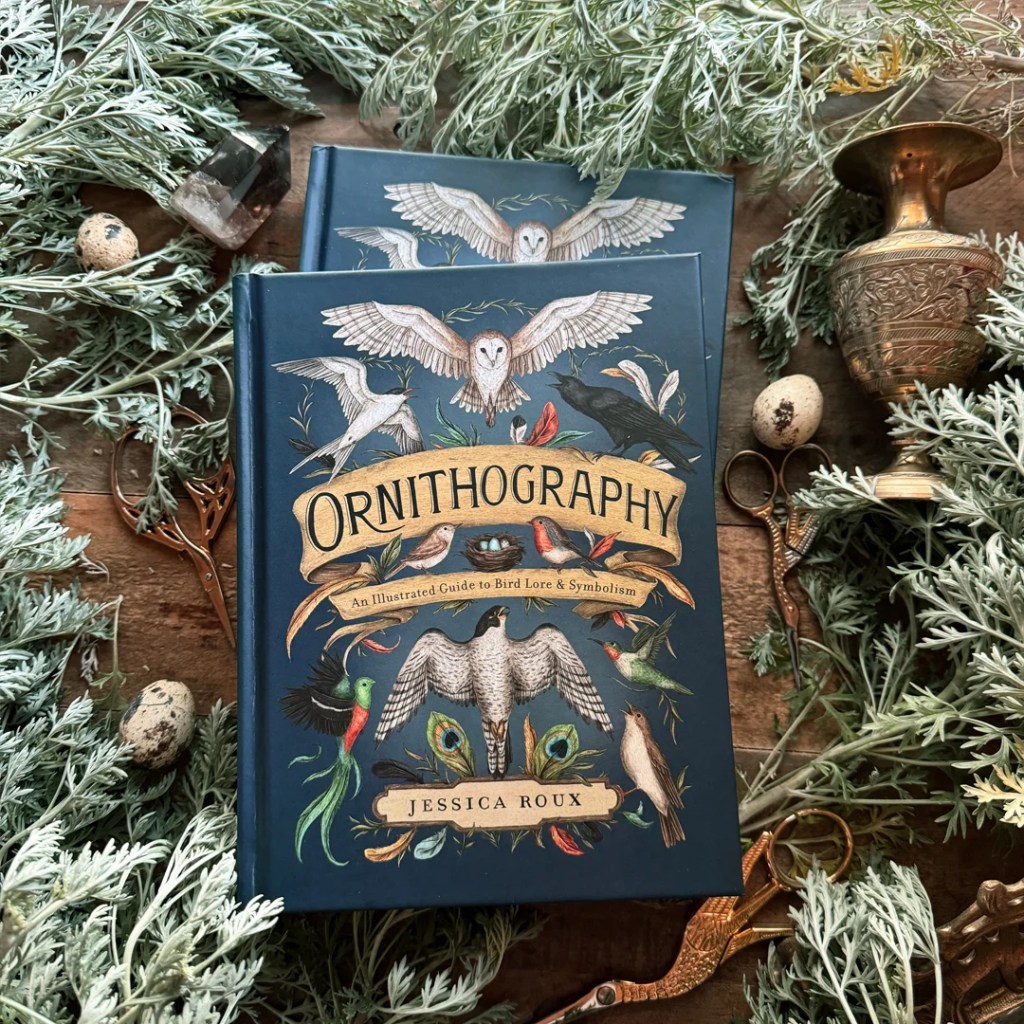

Jessica Roux Illustration

Jessica Roux’s illustration practice infuses the natural world with a mystical, almost otherworldly quality. Her intricate, hand-drawn style transforms flora and fauna into symbolic representations that evoke a sense of wonder, spirituality, and the untamed wildness of nature. The fine details she brings to life in her depictions of plants and animals create a palpable connection between the viewer and the natural world.

This practice inspires me to push the boundaries of graphic design, encouraging me to incorporate elements of fine art and skilled craft into my work, and to explore how the mystical aspects of the natural world can be visually expressed.

In my own practice, I draw from Roux’s ability to portray the natural world not just as it is, but as something that transcends the ordinary, something imbued with a deeper spiritual or emotional essence. This has influenced my approach to designing with animals, plants, and landscapes, where I seek to represent not just their physical form, but the sense of mystery and sacredness they hold.

Roux’s focus on the interplay of natural elements, the wildness of nature, and its untapped spirituality encourages me to move beyond conventional graphic design and explore the boundaries of what is considered “design” or “art.” I aim to create work that speaks to the viewer’s emotions, inviting them to connect with the untamed beauty of the world and reflect on the deeper, mystical forces at play in nature. Through this lens, my work seeks to honour not only the visual appeal of nature but also its spiritual and transformative power.

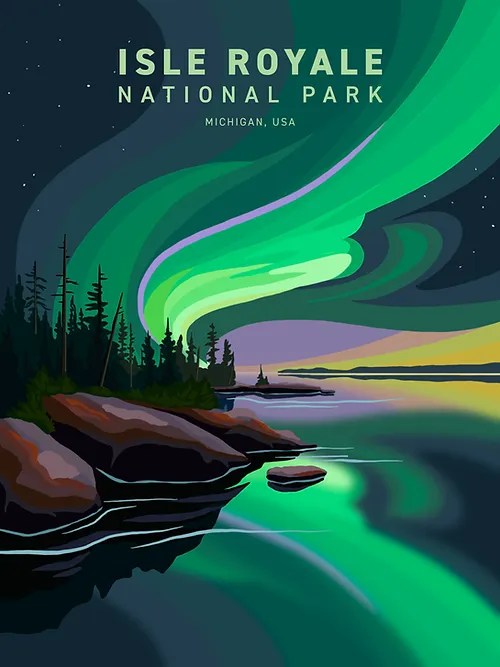

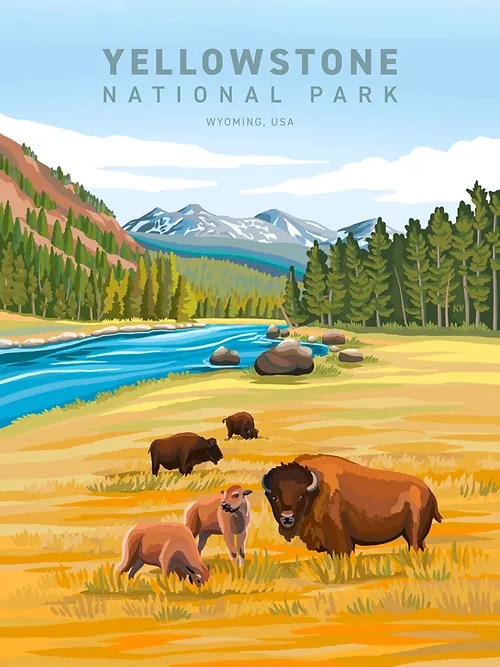

Kelsey Voss: National Parks Artist

Kelsey Voss’ artwork, produced in collaborative with National Parks, USA. captures the sublime in a way that resonates with a contemporary audience: Her professional practice, providing printed merchandise, special commissions and special edition series, nurture the audience’s engagement with nature by promoting, celebrating and commemorating transformative experiences in nature.

Through her intricate depictions of expansive landscapes, Voss conveys both the overwhelming scale of nature and its delicate intricacies, creating a sense of awe that invites contemplation of humanity’s relationship with the natural world. The sublime is expressed in her work not only through vast, imposing landscapes but also through the subtle interaction of light, colour, and texture that suggests both the power and fragility of nature. This duality evokes a sense of awe that challenges viewers to reflect on their own insignificance in the context of the overwhelming vastness of nature. Her use of expressive colours reminded me of the fauvist art movement, where bold brush strokes and exaggerated palettes express the emotional perspective of the artist.

Voss’ work serves highlights the importance of preserving these wild spaces, speaking to a contemporary audience feeling disconnected from the natural environment or disempowered and anxious about ecological issues. The sublime in her pieces is not only a call to appreciate the beauty of nature but also a subtle critique of humanity’s impact on it. Through this exploration, Voss’ National Parks artwork offers a contemporary reimagining of the sublime, blending traditional themes with modern concerns about conservation and environmental stewardship. In doing so, she provokes a renewed sense of reverence and urgency in her audience, encouraging a deeper engagement with the natural world and its protection.

Dragon: Sublime Symbolism

The dragon motif can symbolize both the destructive and transformative aspects of climate change while also evoking deeper themes of the sublime, human fragility, and mortality. Inspired by my grandparents’ practice, the dragon can act as a visual reference to the unknown and the terror associated with nature’s power. The dragon’s fire, often linked to destruction, mirrors the visceral threat of environmental disasters like wildfires and climate crises, as echoed in Greta Thunberg’s phrase “Our House is on Fire.” This symbolism connects the dragon to the immediate urgency of environmental change, highlighting humanity’s vulnerability in the face of these crises.

Additionally, the dragon serves as a multidimensional metaphor for nature in a contemporary context. It represents the raw power of the natural world and the fragility of human identity, urging reflection on our relationship with the Earth. The dragon’s destructive force also hints at the potential for transformation and renewal, calling for a shift in how we engage with the environment. Through this lens, the dragon encapsulates both the terror of climate disaster and the hope for regeneration, reminding us of the need to restore balance with nature.

Design Experimentation

Not being satisfied with the initial design I explored dystopian imagery suggesting themes of decay and destruction relating to the dragon without visually referencing it at this point.

In this design I used strategically coloured moths to suggest ecological themes of fire, ice and earth, which seemed to add an ethereal quality contrasting with the decaying elements in the background. I feel that this provided a more interesting aesthetic but could be developed into a series of patterns/ prints each with a specific ecological focus.

Animal Subjects of Sublime

Dvaledraumar is a musical collaboration between Scandinavian artists, Wardruna and Jonna Jinton, exploring the sublime through ethereal sounds and powerful symbolism. The piece explores the idea of the bear in hibernation, evoking both awe and terror, symbolising the raw, untamed forces of nature. Jinton’s ethereal ‘earth sounds’ capturing the cracking and rumbling sounds of lake turning to ice adds a haunting other worldly dimension, capturing the tension between stillness and latent power.

The sounds of ice are created through its expansion and contraction in response to temperature fluctuations, causing cracking and creaking. Water seeping into the ice and refreezing creates pressure, leading to deep rumbles and high-pitched crackles. The layers of ice produce complex sounds that evoke the primal, visceral forces of nature, much like the dormant bear, which holds immense potential for life and movement beneath the surface.

Jinton also explores the phenomenon of ice sounds through her visual art. Merging sound with photography and painting, she captures the textures, colors, and ethereal qualities of ice. Her visual work translates the frozen landscape into images that evoke mystery and stillness, amplifying the profound connection between nature and human perception. Through this cross-disciplinary approach, she offers a holistic experience that incorporates both the sound and visual beauty of ice.

Through Dvaledraumar, Jinton and Wardruna evoke nature’s awe-inspiring and terrifying forces, reminding us of our vulnerability and the urgency of respecting the environment. Being passionate about animals, the thematic exploration of the bear inspired me to consider animals as subjects evocative of the sublime. William Blake’s The Tyger (1794) similarly explored the tiger as a romantic metaphor for universal duality of beauty and destruction.

I aim to do this is a way that engages the viewer emotionally from a primitive perspective, whilst providing aa layer of ecological criticism and emphasizing the need to protect nature from further harm.

Hagley Falconry Centre (Photography)

Reflecting on Blake’s The Tyger (1794) and Wardruna’s exploration of the bear as a source of the sublime, I’ve decided to study birds of prey, which have long inspired my artistic work.

Birds of prey embody the sublime through their powerful presence, beauty, and predatory nature, evoking both awe and fear. Their ability to fly symbolizes freedom and transcendence, reminding us of the raw, uncontrollable forces of nature.

For this reason, the falconry centre attracts local artists, some of whom display prints and original artworks in the centre’s gift shop. While I appreciated the work on display, I felt it didn’t fully capture the depth of the birds’ presence, which inspired me to explore them visually in my own way and potentially collaborate with the centre.

With an art background influenced by Renaissance painting, I felt compelled to express my interpretation of these subjects in a way that observes their fine detail while emotionally communicating their significance to humans.

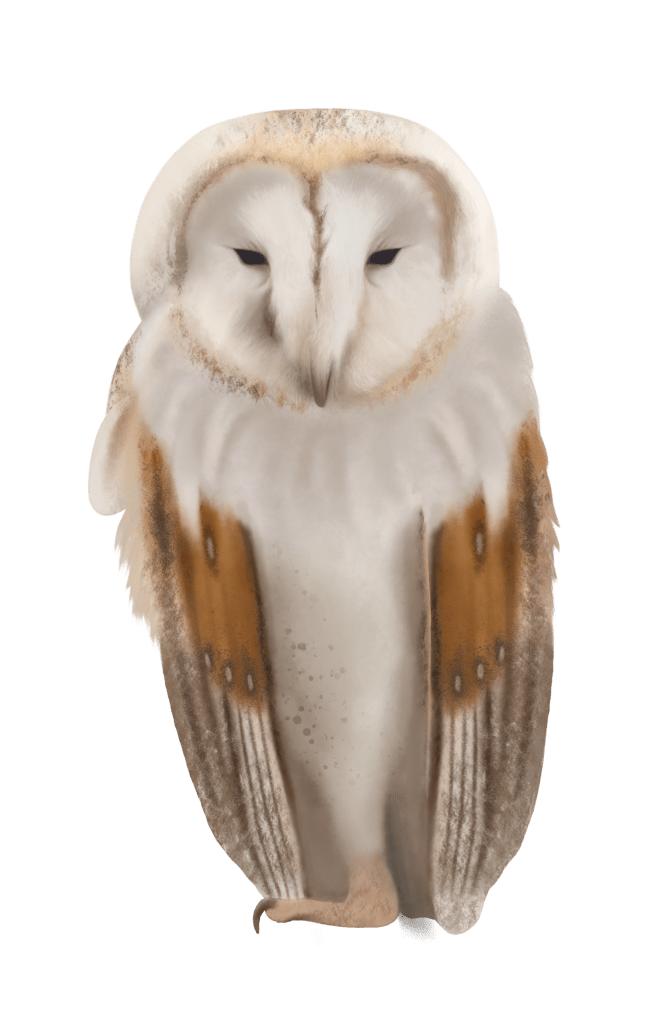

Design Experimentation: Digital Painting

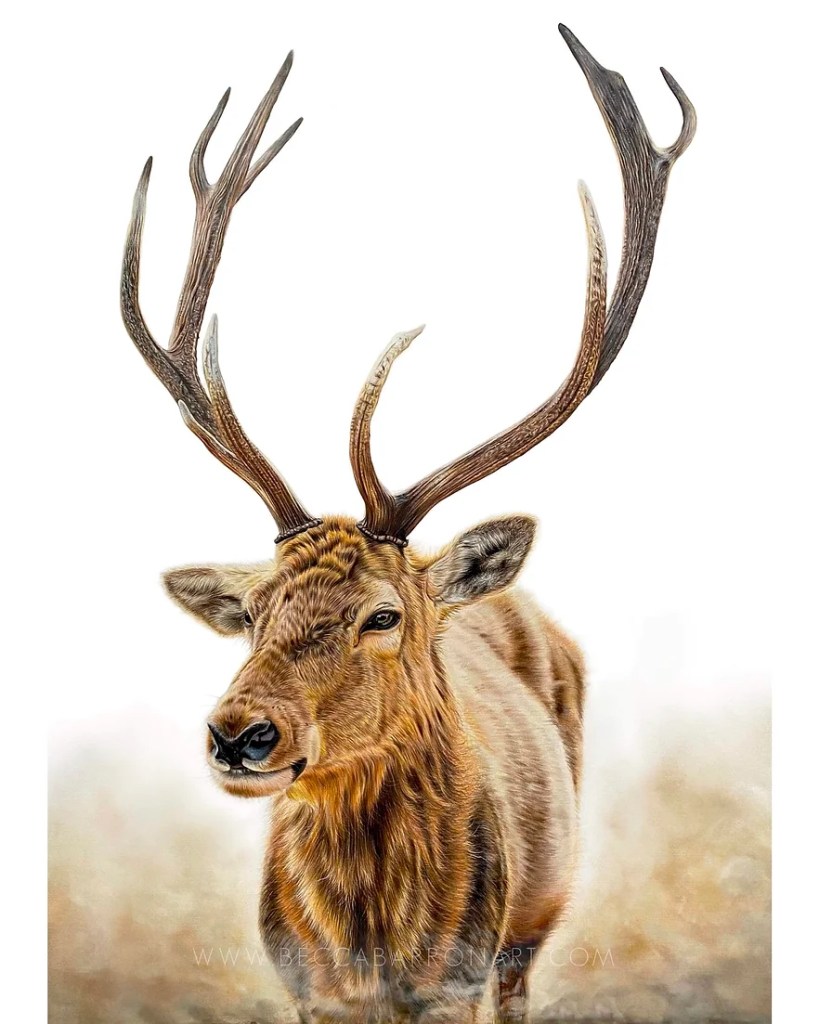

Becca Barron: Pet Portrait & Wildlife Artist

At this stage of the project, I found it impossible to overlook artists like Becca Barron, whose practice is dedicated to the observation of animals through classically inspired, skill-based portraiture and figurative representation. Barron’s work highlights a consumer demand for personalized pet portraits and an appreciation for sensitively rendered, naturalistic studies of wildlife, often found in fine art prints or as part of stationery and homewares.

Having a background in this style of working, which I was initially discouraged from pursuing during my time as a fine art undergraduate, I was forced to reconsider the function of figurative representation. I questioned whether I had been trying to force my work into a context that didn’t align with my strengths or creative impulse.

This led me to the question: How can I use my skills in naturalism and detail to meaningfully explore contemporary themes and animal/ natural subject matter? And can I work in a way that capitalises on high levels of detail?

Reconnecting with painting

After reflecting on my previous experience of figurative painting, I felt compelled to reconnect with the medium, driven by a desire to re-evaluate my relationship with process and the tactile nature of the final outcome. This exercise reminded me of Tracey Emin’s comment that small paintings for her felt intimate, “like kissing”. Through representation and naturalism, I approached painting as a cathartic act of immortalisation, attempting to overcome the limitations of the human condition by capturing moments and transcending mortality.

This process reminded how time-consuming painting could be but also how raw and mindful. Having not painted in oils for over 5 years this was an extremely significant and somewhat intimidating experience for me, but one revealed how important painting is to me as I became frustrated and ashamed by my lack of practice.

For instance, I noticed feeling timidity and hesitancy with the use of colour and brushwork, where I had once been able to use marks much more confidently and gesturally to create likenesses to my subject. This led me to research and observe painters who worked in a representational way but had a more expressive and confident approach to aspire to, which also allows for a deeper level of ambiguity and interpretation of the artists hand.

The clumsy studies served as an experimental exercise to re-engage me into the world of painting. Unlike digital painting this this highlighted the importance of preliminary composition sketching, leading me to consider how I could use photography and digital manipulation to generate mock ups of more surreal and symbolic imagery. However, this then led me to the question, why, then, is the physical painting worthwhile?

This led me to question painting’s relevance in contemporary art. An article from BBC Culture titled “Is painting dead?” (2015) echoes this sentiment, which I found myself grappling with in my own practice. The tension between digital and traditional mediums reflects wider shifts in art, prompting me to reflect on how I can combine both approaches to express contemporary themes while preserving the cultural and emotional significance of the painter’s hand.

Colour symbolism

Having explored dragons as an environmental motif symbolising destruction and sublime forces of nature, I realised that the colour red has been a reoccurring theme in my analysis of art and design for many years. For example, In Blake’s The Tyger (1794) The Tyger being forged in flames is a metaphor for universal creations dual potential for beauty and destruction.

Mark Rothko’s Red on Maroon and Mark Quinn’s Self (1991) also use red to reference their works focus on both life and death. Red on Maroon was created with a glazing effect that gives the viewer the impression that the square opening is physical pulsating, creating a sense of ambiguity which could be interpreted as the void before or after the experience of being (pre-conception and after death). Wardruna and Richard Moss also use the colour red in their contemporary work, investing their subject matter with otherworldly qualities.

Animals in the Anthropocene

Having identified a pattern of highly influential artworks using the colour red, I wanted to experiment with this through a series of animal portraits exploring the concept of fire to refence the urgency of climate change and the self-destructive capacity of human kind in relation to our relationship with the natural world.

At the outset of this project, I was encouraged to make it personal, as it would serve as a springboard into my creative career as an MA graduate. As a result, I recognised that my studio practice would need to focus on developing my personal brand and refining my creative identity.

However, this presents a series of challenges. Should I register my freelance practice under my own name or adopt a brand name? Additionally, should I separate my marketing materials into distinct identities—one for fine art and one for graphic design? Or would it be more effective to position myself as a multidisciplinary creative with expertise in specific areas? If I take this latter approach, would this make my target audience more complex to define and reach?